New research has claimed that the bluestones at Stonehenge did not come from a prehistoric giant lost circle in the Preseli hills.

The bluestone monoliths incorporated into the famous prehistoric monument of Stonehenge did not come from a “giant lost circle” at Waun Mawn in West Wales.

That is the conclusion reached in new research published today in the international “Holocene” journal.

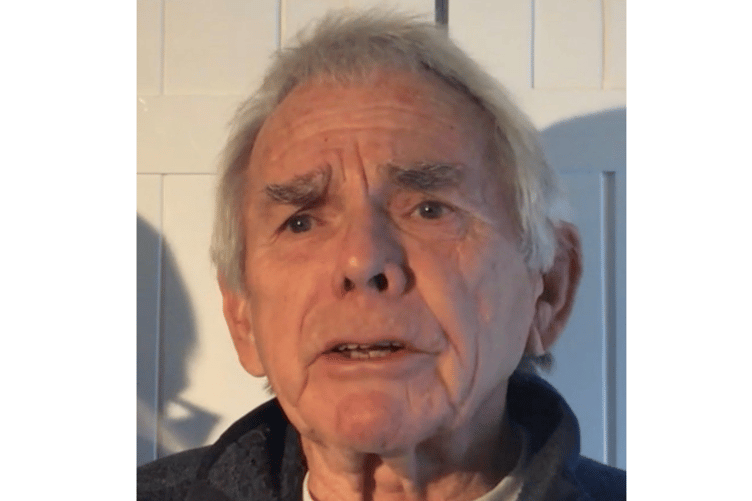

Researcher Dr Brian John, who lives close to the site in question, has examined the evidence associated with the claim that around 5,000 years ago scores of bluestones were incorporated into a massive stone setting on a bleak moorland hillside in the Preseli mountains.

He finds that the field evidence does not withstand scrutiny.

Nor does he find any evidence to support the hypothesis that the stones were later dismantled by our Neolithic ancestors and moved cross country to be reassembled on the chalk-lands of Salisbury Plain.

The narrative of bluestone quarrying, temporary placement at Waun Mawn and human transport to Stonehenge has been developed over the past decade by Professor Mike Parker Pearson of University College London and a team of archaeologists and geologists.

Excavations have been concentrated at two “quarrying” sites and also at Waun Mawn, where digs were conducted on common land in the years 2017, 2018 and 2021.

The “bluestone quarrying” sites described by the archaeologists are at Craig Rhosyfelin near the village of Brynberian and at Carn Goedog, on the north-facing slope of Mynydd Preseli. At the former, the rock type is rhyolite, and at the latter, spotted dolerite.

Extensive excavations by Parker Pearson and his team have resulted in multiple publications, with extravagant claims of monolith quarrying “on an industrial scale”.

Dr John and colleagues have studied both sites in detail, and have determined that the “engineering features” describes are entirely natural in origin. They dismiss the idea that there was prehistoric quarrying for monoliths at either site

Scores of papers have been published by the team, and their narrative has been widely publicised in the media, including TV documentaries.

At present there is only one standing stone on the Waun Mawn site, with three recumbent stones in a rough alignment.

Dr John claims that it is fanciful in the extreme to interpret this rough stone setting as the last remnant of one of the biggest stone circles in the British Isles.

He has examined most of the supposed empty “stone sockets”, and concludes that they are entirely natural pits and hollows in a surface of undulating glacial and periglacial deposits.

He finds no evidence of a circular arrangement. He also disputes the idea that monoliths of rhyolite and spotted dolerite from the supposed “quarries” of Rhosyfelin and Carn Goedog were brought to Waun Mawn, and he sees no evidence that these stones were deemed sacred or special in any way.

He says that all of the stones currently found at Waun Mawn have come from local outcrops of rock and from a scatter of glacial erratics.

Further, he disputes the idea that one of the stone sockets was a precise “fit” for one of the standing bluestones at Stonehenge.

Dr John said: “The conclusion must be that Waun Mawn had nothing at all to do with Stonehenge. “There were no stone quarries in the vicinity, and there was no lost stone circle.

“Unfortunately, the archaeologists have been swayed by the false premise that the Stonehenge bluestones (from many different sources) cannot possibly have been transported by glacier ice; and on that basis they have developed a highly complicated ruling hypothesis of bluestone extraction and use whilst ignoring the very flimsy nature of their own evidence.”

Dr Gordon Barclay and others have pointed out that an obsession with finding “Stonehenge links” has been ultimately damaging to prehistoric archaeology in the British Isles, with Dr John adding: “There were many Neolithic cultures and landscapes in Britain, and it is most likely that the tribes of West Wales had no knowledge whatsoever of events far to the east, on Salisbury Plain.”

In the newly published article Dr John points out that in the Neolithic and Bronze Age landscape of West Wales there is no evidence of spotted dolerite and rhyolite bluestones being used preferentially in megalithic structures.

He also notes that in their latest publications Prof Parker Pearson and his team have accepted that many of their assumptions about bluestone extraction and use in West Wales need to be revised.

Dr Brian John is a retired geomorphologist and university lecturer who has published widely on the landscapes of the polar regions and on the glaciation of Wales. He is joint author (with Professor David Sugden) of the classic university textbook entitled “Glaciers and Landscape” which remained in print for 30 years. John Glacier in Antarctica was named after him in recognition of his contributions to polar research.

The latest claims fly in the face of a study conducted in 2019 by a UK research team who excavated two quarries and claimed there was evidence of megalith quarrying 5,000 years ago.

The study, published in the journal Antiquity pinpoints the exact locations of two of these quarries and reveals when and how the stones were quarried.

The discovery was made by archaeologists and geologists led by UCL – working the University of Southampton, Bournemouth University, the University of the Highlands and Islands and the National Museum of Wales. The team investigated the sites over an eight year period.

The largest quarry was found almost 180 miles away from Stonehenge on the outcrop of Carn Goedog, on the north slope of the Preseli hills. This was the dominant source of Stonehenge’s spotted dolerite, so-called because it has white spots in the igneous blue rock. At least five of Stonehenge’s bluestones, and probably more, came from Carn Goedog.

In the valley below Carn Goedog, another outcrop at Craig Rhos-y-felin was identified by Dr Richard Bevins (National Museum of Wales) and fellow geologist Dr Rob Ixer (UCL) as the source of one of the types of rhyolite – another type of igneous rock – found at Stonehenge.

Speaking at the time, Leader of the team, Professor Mike Parker Pearson of UCL said: “What’s really exciting about these discoveries is that they take us a step closer to unlocking Stonehenge’s greatest mystery – why its stones came from so far away.

“Every other Neolithic monument in Europe was built of megaliths brought from no more than 10 miles away. We’re now looking to find out just what was so special about the Preseli hills 5,000 years ago, and whether there were any important stone circles here, built before the bluestones were moved to Stonehenge.”

Archaeologist Dr Joshua Pollard of the University of Southampton added: “This research is further confirmation that the Stonehenge bluestones were moved in prehistory by people, rather than by geological forces such as ice-sheets. The transportation of these massive slabs of rock stands out as one of the most remarkable instances of long-distance movement of large stones in the ancient world.

“This demonstrates how early farmers, settled in what is now Wiltshire, had a strong connection to their ancestral lands in Wales and needed to reinforce those connections through the movement and building of a great megalithic monument.”

According to the study, the bluestone outcrops are formed of natural, vertical pillars. These could be eased off the rock face by opening up the vertical joints between each pillar. Unlike stone quarries in ancient Egypt, where obelisks were carved out of the solid rock, the Welsh quarries were easier to exploit. Neolithic quarry workers needed only to insert wedges into the ready-made joints between pillars, then lower each pillar to the foot of the outcrop.

Although most of their equipment is likely to have consisted of perishable ropes and wooden wedges, mallets and levers, they left behind other tools such as hammer stones and stone wedges.

Archaeological excavations at the foot of both outcrops uncovered the remains of man-made stone and earth platforms, with each platform’s outer edge terminating in a vertical drop of about a metre. Bluestone pillars could be eased down onto this platform, which acted as a loading bay for lowering them onto wooden sledges before dragging them away.

An important aim of the research was to date megalith-quarrying at the two outcrops. In the soft sediment of a hollowed-out track leading from the loading bay at Craig Rhos-y-felin, and on the artificial platform at Carn Goedog, the team recovered pieces of charcoal dating to around 3000 BC.

The team believed Stonehenge was initially a circle of rough, unworked bluestone pillars set in pits known as the Aubrey Holes, near Stonehenge, and that the sarsens (sandstone blocks) were added some 500 years later.

The 2019 discoveries also cast doubt on a popular theory that the bluestones were transported by sea to Stonehenge – taken southwards to Milford Haven, paddled up the Bristol Channel and along the Bristol Avon towards Salisbury Plain. But these quarries are on the north side of the Preseli hills, so the megaliths could have gone overland to Salisbury Plain.

Late last year, researchers from Aberystwyth University cast doubt over the origin of the largest bluestone at the heart of Stonehenge.

For the past 100 years, the six-tonne Altar Stone was believed to have come from Old Red Sandstone in south Wales.

This was assumed to be close to the Preseli hills in west Wales where the majority of Stonehenge’s world-renowned ‘bluestones’ came from.

Formed when molten rock crystallised, the Pembrokeshire bluestones are believed to have been among the first erected at the Wiltshire site around 5,000 years ago.

The Altar Stone, a sandstone, has traditionally been grouped with the other, smaller, igneous bluestones, although when it arrived at Stonehenge is unclear.

Now, in an attempt to locate its source, scientists at Aberystwyth have compared analyses of the Altar Stone with 58 samples taken from the Old Red Sandstone across Wales and the Welsh borders.

The composition of the Altar Stone cannot be matched with any of these locations. The Al-tar Stone has a high barium content, which is unusual and may help in identifying its source.

Professor Nick Pearce from Aberystwyth University said: "The view in terms of the conclu-sions we've drawn from this is that the Altar Stone doesn't come from Wales. Perhaps we should also now remove the Altar Stone from the broad grouping of bluestones and consider it independently.

“For the last 100 years the Stonehenge Altar Stone has been considered to have been derived from the Old Red Sandstone sequences of south Wales, in the Anglo-Welsh Basin, although no specific location was identified.

“The Altar Stone appears not, in fact, to come from the Old Red Sandstone of the Anglo-Welsh Basin - it is not from south Wales.

"Attention will now turn to the other areas, like northern England and Scotland, areas where the geology is right, the chemistry is right, and Neolithic activity is present, to ascertain whether any of these sandstones have characteristics which match the Stonehenge Altar Stone.”

Professor Pearce added: "Hopefully these findings will help people to start looking at the Altar Stone in a slightly different context in terms of how and when it got to Stonehenge, and where it came from. Hopefully this will lead to some new thoughts about the development of Stonehenge.”

English Heritage describes Stonehenge as a masterpiece of engineering, built using only simple tools and technologies, before the arrival of metals and the invention of the wheel.

Building the stone circle would have needed hundreds of people to transport, shape and erect the stones.

These builders would have required others to provide them with food, to look after their children and to supply equipment including hammerstones, ropes, antler picks and timber.

Whatever the truth is around the genesis of the UNESCO World Heritage site, its existence is sure to attract debate and claims for years to come.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.