A longstanding trope of LGBTQ+ stories is that rural queer folk must flee to the safety and comfort of a city.

Finding the metropolis an anonymising space, they can live without discrimination and find others like them.

But what about the country queers who believe, despite stereotypes, that no place is like home, who long for community as much as they do a life in their village?

Similar to the LGBTQ+ mecca that is Yorkshire’s Hebden Bridge - full of queer artists and their families - small pockets of communities in Mid-Wales’ Machynlleth, Llanbrynmair, Aberystwyth and across Ceredigion are becoming answers to that question.

Machynlleth is known to have a thriving LGBTQ+ population, whilst it was Aberystwyth, not Cardiff, hailed as the gay capital of Wales after the 2021 census.

More than 16.5 per cent of those aged 16 and over in Aberystwyth North identified as LGB+, beating both Bangor City and two Cardiff areas.

Ceredigion also has the highest concentration of adults (0.7 per cent) - equal to Cardiff - who identified as transgender.

Many attribute the Dyfi Valley’s welcoming attitude to the alternative thinking encouraged with the establishment of the Centre for Alternative Technology in 1973.

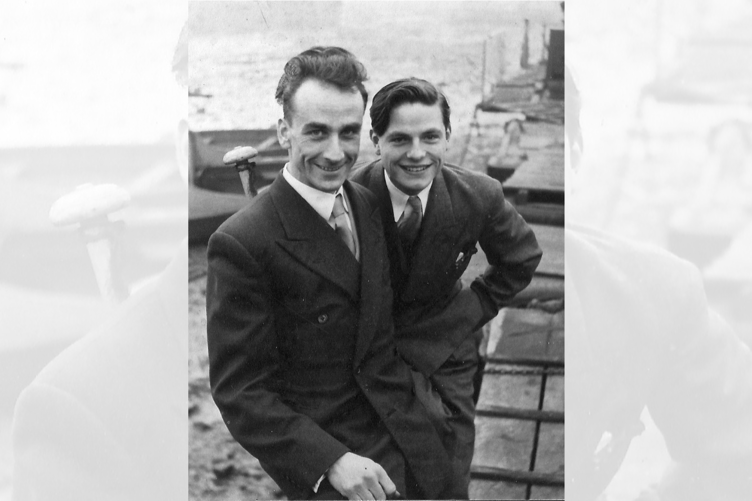

Just a year earlier, pioneering queer couple Reg and George arrived in Machynlleth, living the rest of their lives open and peacefully after enduring the first 18 years of their relationship in secret due to the criminalisation of homosexuality.

In 2006, they celebrated their love with the town’s first same-sex civil ceremony.

In similar strides, May saw Machynlleth host its first Pride - the town, dripping in rainbows, moved some residents to tears with the sight of their home in visible celebration of their lives.

Aberystwyth celebrated its second LGBTQ+ Pride along the prom this April.

Despite Reg, George and other rural LGBTQ+ people, the introduction of Section 28 meant they were often still invisible to young people.

Sienna Holmes, 29, a Mach Pride organiser, said: “Growing up [in the Dyfi Valley] I didn't see myself or my queerness reflected in the community around me.

“It made me believe I had to leave to find it.

“Since returning, my experience has motivated me to create spaces I didn't have access to.

“In a small town, it is important to ensure everyone is welcomed and celebrated for their diversity- we are all responsible for co-creating our community.

“Mach Pride was a powerful affirmation of love, identity, and the enduring allyship of our community.”

Cierra, 21 from Caernarfon, no longer speaks to most people from her home town - having been physically and verbally assaulted at 17 for being who she is, she left her home behind in search of community in Aberystwyth.

The criminology graduate, 21, said: “Moving to Aberystwyth has helped me become myself.

“I was able to surround myself with openly trans and queer people for the first time.

“Back home, there were no openly LGBTQ+ people but in Aber, there are lots of people from different backgrounds.”

Many friends from home have moved away due to lack of opportunities, and having cut off family members who aren’t accepting, she finds fewer reasons to go back.

She said that if she’d had access to resources helping her understand her gender identity earlier, it may have helped her feel less isolated.

Rural queer lives have always existed but rarely feature in history books - lack of money or legal recognition meant LGBTQ+ couples aren’t recorded in the land registry, and embarrassed family members meant diaries like 1800s lesbian Anne Lister are hard to come by (many of hers were burned by her relatives).

The Ladies of Llangollen are an exception - living together in the late 1700s in their grand house in north Wales after defying the will of their families.

Former Plaid Cymru candidate for Ceredigion Mike Parker wanted to preserve these stories by writing about his late friends Reg and George in his book On the Red Hill: “I wanted to mark what progress looked like.

“So many queer lives have vanished- often with no children to carry a legacy, ostracised by family, we existed in the margins of history - when we die our stories vanish.”

So, why do LGBTQ+ people feel drawn to Mid-Wales?

Mike, 57, was a travel writer in the 90s when he stumbled upon Machynlleth’s free party scene.

He moved in 2000 after the launch of the internet, which felt like a safety net as a single queer man, but he didn’t need it- bumping into a handsome man in the wholefood shop who became his lifelong partner: “I wouldn’t have met Preds if I hadn’t moved here- he’s a local, he wasn’t going to any of the Birmingham gay clubs.”

Mike said though there weren’t as many LGBTQ+ people here then as there are now, the place felt innately queer: “I was told by my city friends I’d be hung, drawn and quartered at worst, and at best never have sex again.

“I knew this was wrong but have struggled to put my finger on why.

“Wales is a minority culture- minority cultures recognise each other, the same stuff gets thrown your way.

“Machynlleth has always been a crossroads - that’s why Glyndŵr had his parliament here - meaning there’s a constant diversity of life- that’s the beat of this place.”

Sarah Wilson moved to Llanbrynmair with her wife six years ago, incidentally to “a road with 10 lesbians”, after visiting friends and discovering the same parties as Mike.

The shiatsu practitioner, 51, said: “The parties were not queer but always queer friendly- it just wasn’t a big deal.

“When I started going out in early 90s Birmingham, the gay scene was controlled by white rich gay men - we’d have to be signed in by male members.

“It was difficult to be both black and queer there.

“Moving here, I quickly saw there were a very supportive group of queer people who were good at holding each other.

“Other queer communities can be more fractured and, of course, there are difficulties in all communities, but there’s a difference here in how well they work through issues by talking about it and a willingness to do so.

“I think it makes people feel safer to be who they are.”

Though a 2017 ONS survey found most LGBTQ+ respondents lived in London, Manchester and Brighton, many articles have since evidenced anecdotes of LGBTQ+ people returning to their rural roots.

The stereotype of rural communities being bigoted applies across all countries, not just Wales- however those who spoke to the Cambrian News reported experiencing little homophobia, though “microaggressions are, of course, everywhere”.

Transphobic sentiments however are still a concern, with a transphobic road sign seen on the A487 last summer.

Cierra said: “I do think there are still barriers here.

“Sometimes I still have to watch my back in Aber- especially at a bar.

“I’ve received transphobic abuse a couple of times there.”

Home Office data reveal homophobic hate crimes reported to the Dyfed-Powys police increased steadily from less than 50 incidents in 2017/18 to over 100 in 2021/22.

Dyfed-Powys recorded 34 hate crimes against transgender people in 2022/23 – a rise from 25 in 2021/22, while North Wales recorded 61 in the same timeframe – up from 50 the previous year.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.