A bomb was made out of a Horlicks tube in a bid to derail Prince Charles’ investiture in Caernarfon by a man dubbed “The Barnes Wallis of Wales.”

But the device, created to free the Welsh from the “English yoke,” barely caused a ripple when it was tested, leading the Free Wales Army (FWA) and its self-proclaimed leader, Cayo Evans, from Silian near Lampeter, back to the drawing board.

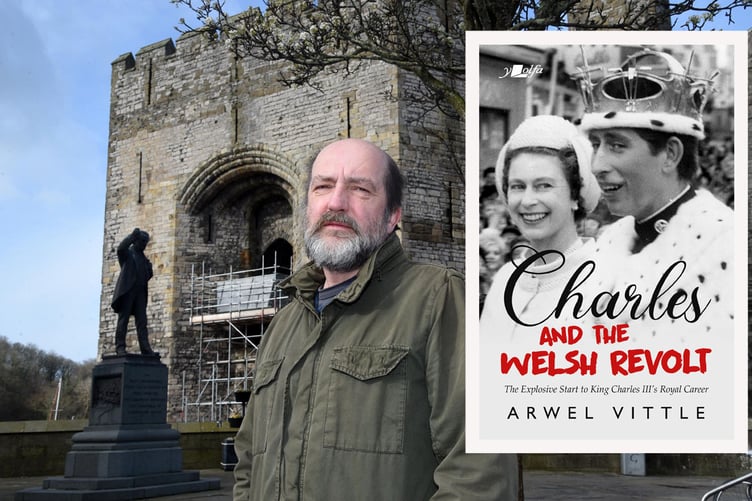

The anecdote, told by Pontrhydfendigaid journalist Lyn Ebenezer, features in a new book called Charles and the Welsh Revolt by author Arwel Vittle who was raised in Carmarthen and now lives in Caernarfon in Gwynedd.

The book explores the explosive start to King Charles III’s royal career and how, according to nationalists, the “archaic and oppressive (royal) tradition has been a blight on the nation for centuries,” since Edward I deposed the last native Prince of Wales, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1282.

It also details the bizarre plots which included “kamikaze dogs” and manure to disrupt the 1969 ceremony at Caernarfon Castle, which also saw four other bombs planted by the militant group, MAC (Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru).

The contribution to Vittle’s book from Ebenezer recalls travelling to a remote area with Evans in the run up to the royal proceedings.

“What was there was about 20 FWA lads testing a new bomb,” Ebenezer says.

“The bomb had been made out of a Horlicks tube and the guy who made the bomb lived in Llangollen.

“Cayo introduced him as ‘The Barnes Wallis of Wales,’ whose bomb is going to release us from the English yoke.”

Barnes Wallis was an English engineer and inventor best known for inventing the bouncing bomb used by the Royal Air Force during World War II.

Recalling the bomb being tested, Ebenezer remembers taking cover behind a stone wall.

“I saw the smoke rise from the bomb in the wall, and then after a few seconds came a noise: ‘Pffft.’

“A cloud of smoke rose up but no stone was dislodged! Sheep were still quietly grazing and none raised their heads. And I remember Cayo’s words clearly: ‘F**k it, boys – back to the drawing board!.”

The FWA first appeared in public at a 1965 protest against the construction of the Llyn Celyn reservoir near Bala.

On one occasion, an FWA member fitted a harness to his dog, which he said would be used to carry sticks of explosive gelignite.

He had dozens more dogs all trained to carry magnetic devices under Army vehicles.

The story about these “kamikaze dogs” duly appeared in newspapers and prompted hundreds of angry letters from dog-lovers.

Another “plot” included hiring a helicopter to drop farmyard manure on the Prince of Wales’ investiture.

The consequence of the stunts and exploits of the FWA diverted attention from the “real bombers,” the MAC, masterminded by John Jenkins who was radicalised by the drowning of the Tryweryn Valley above Bala.

The Welsh nationalist and British Army soldier was jailed for 10 years for organising explosions in a campaign of sabotage against the investiture. One device exploded unexpectedly killing two members of the MAC in Abergele.

The following day, two more bombs were planted in Caernarfon. One exploded in a police constable’s garden during a 21-gun salute.

Another was planted at Llandudno Pier where the Royal Yacht Britannia was expected to moor, but did not go off.

The second Caernarfon bomb was found by a 10-year-old Buckinghamshire boy playing football while on holiday, who lost part of his leg when it exploded.

The late Jenkins is quoted in Vittle’s book as saying: “How the hell do you expect people to celebrate their own defeat?

“To celebrate the fact in the last 700 years, we hadn’t moved forward an inch and had moved back a couple of yards.

“To commemorate it is one thing, but to celebrate it is another story.”

Jenkins adds: “The only way to be heard is to kick up a fuss. And you’ve got to kick up a fuss that really threatens.

“That’s why we had to make direct threats to Charles. They were never meant to be carried out, of course. What would be the point of the political fallout from killing him?”

Arwel Vittle, who runs a translation company, said it was “interesting” to hear the first hand accounts of the activists and extremists at the heart of the protest movement.

“It was a tense time not only with the bombing campaign, but also Cymdeithas yr Iaith’s non-violent protests and large rallies and Plaid Cymru getting its first electoral successes. I wanted to look at what caused this extreme reaction around Charles’ Investiture, whether it was worth it, and whether it could all happen again.”

The father-of-three and author of popular histories, including I’r Gad, a photographic history of Welsh language protests, and Valentine, a biography of Lewis Valentine, the first president of Plaid Cymru, said: “I thought it would be interesting to look at Charles’ formative years in public life as Prince, which started with a bang as it were, because of the political atmosphere in Wales, which at the time was pretty febrile.

“With Charles becoming King and his coronation yet to take place, I wanted to write a popular history book which was a good read as well as informing.

“Speaking to many participants, it was good to hear first-hand, what it was like to be part of that period – things that aren’t documented in many other history books.

“Many hadn’t spoken out about their experiences before – particularly around the secret police and surveillance – some people compared Gwynedd at the time to being like a police state like East Germany and (the then) Czechoslovakia – it was interesting to lift the lid on that.”

• Charles and the Welsh Revolt is published by Y Lolfa.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.