In a hamlet on the A487 between Aberystwyth and Machynlleth, you can find the “best-preserved charcoal-burning blast furnace of the 18th century in Wales” – The Dyfi Furnace.

Wales’ industrial past is well documented, with the north being known for its slate mines and the south for its iron and coal deposits. But the history of the heart of the country can be overlooked.

Although it didn’t have slate, iron or coal like other parts of the country, mid Wales had an abundance of natural resources that made it equally as industrious during the time.

The company Vernon, Kendall & Co was well aware of these natural resources and the benefits they could provide for the company’s heavily iron-dependent industry.

With forests enveloping it on all sides and the river Einion running through its centre with enough force to turn a 30-foot water wheel, the hamlet was the perfect site for a charcoal-based blast furnace.

Iron ore had to be shipped over 200 miles from Cumbria, arriving by boat in ports along the Dyfi estuary, or in Aberystwyth itself, before they were pulled by horse-drawn carriage up to Furnace.

In a world where industry was coming to a halt thanks to shortages of charcoal, the company took a risk when it built the Dyfi Furnace over 250 years ago in 1755. They hoped this remote furnace could be the key to making the increasingly valuable – and increasingly difficult to produce – iron.

Trees and water weren’t the only things needed at the furnace, smelting iron also took manpower. Working in the furnace was ‘tough and dangerous’ work, with labourers putting their necks, and plenty of their limbs, on the line every day.

Cadw, the Welsh heritage and environment service, says: “Work here would have been tough and dangerous – lifting and moving heavy loads and operating the blast furnace in extreme heat and with scant regard for health and safety!”

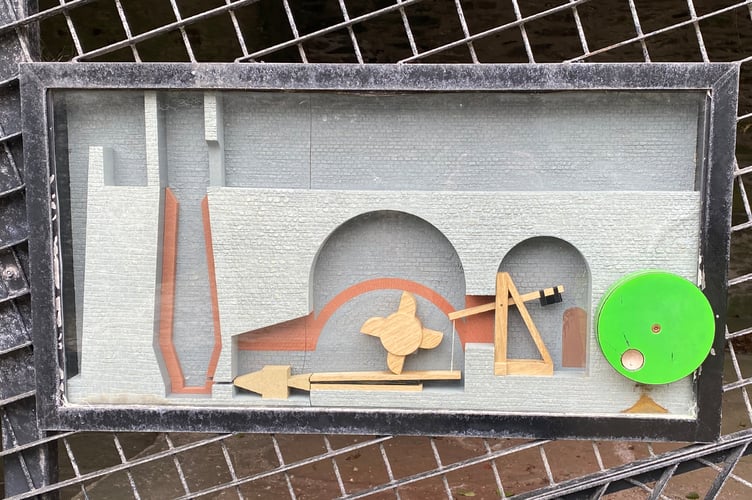

The work began with the damming of the river Einion. Damming the river created a pool which gave the furnace a constant supply of water. When the furnace was in use, or ‘blast’ as it was called, water would be let out of this pool through a leat and pour onto the 30-foot water wheel with enough force to get it to turn and ‘pump the bellows’.

The vast supplies of trees surrounding the furnace made it easy for workers to get their hands on charcoal, a crucial fuel in iron smelting, because it was the only thing which burned hot enough to melt the ore.

The Dyfi Furnace could produce about 150 tons of iron every year.

Once iron was made, the shipping process would then begin again. Horse-drawn carriages would ship the iron back to a harbour and a ship would then carry it across the sea and up the rivers, back to the company’s Midland factories.

Despite the immense amount of movement, and the small amount of iron for that movement, running the Dyfi Furnace was a much better option than importing iron from outside of the UK, but it didn’t leave the company much room for profit.

Only 50 years after it first opened, the Dyfi Furnace closed in 1795.

It was one of the last charcoal-fuelled furnaces to be built in the UK.

And it was completely abandoned by 1810.

But this wasn’t the end of the Furnace’s story.

Sometime after it was first abandoned, the Dyfi Furnace would start its second life as a sawmill.

It was during its second life that the water wheel we see today, stood in the same place as the original, built all the way back in 1755.

Then with the onset of the Second World War and the possibility of a German attack, the site was converted into a machine gun emplacement overlooking the nearby bridge.

Fears of an invasion put the eyes of defence on seaside sites like the Dyfi estuary and Aberystwyth.

A plan was set up to house a machine gun in the furnace and strip out the nearby bridge and fill it with explosives. If any occupying force tried to cross they would be ambushed, cut off and forced to make a difficult retreat along narrow roads; the whole time being sprayed by hundreds of machine gun bullets.

The day where this plan would be put into action never came.

For 30 years, it seemed the tale of the furnace would be left to the annals of history as it was, but that all changed with an article published in 1976.

Written by A O Chater, the article suggested Dyfi Furnace’s life began much earlier than 1755.

It claimed the furnace was built at least 100 years earlier and served a royal duty, requiring not only one water wheel, but four.

Supposedly, Dyfi Furnace was originally a royal mint, sending coins to the then King himself.

Furnace resident Andrew Lewis may hold proof that A O Charter’s claims had more truth in them than you would first expect.

Armed with his metal detector, Mr Lewis went in search of evidence of the royal mint’s existence, having heard stories of it from other locals.

Although he “never expected to find anything”, Mr Lewis’ search would lead him to the very thing he hoped to find.

Mr Lewis managed to find a coin, which he claims was minted at the site.

“I never knew anything about the history here until I started metal detecting a few years ago,” he said. “The mint was only in Furnace for about 12 months during the English Civil War; it was a secret mint for Charles I.

“I’ve been looking for the coins for a while, but I never thought I’d find one. They’re not often found here. It was one of the best things I could have found.

“I’ve got a friend who was able to verify it and it’s definitely what it says on the box.

“There’s lots of stories about the hammer and dye that they used to mint the coins at the site.

“The hammer and dye was used to give coins a distinct feature, typically this was done by pouring melted coins into specifically shaped casts.

“There are stories that there are hammer and dyes still around but no one knows where they are.”

A series of excavations in the 1980s found even more evidence of the site’s royal history.

In 1986, archaeologists found a brick pit, which they claimed “was almost certainly a wheel pit”, but the pit wasn’t below the water wheel we see today, it was somewhere else, indicating it would have been one of the royal mint’s four water wheels.

Today, people may have abandoned the building, but life has not left the 400-year-old Furnace.

It is now home to one of the rarest species of bats in the UK – the Lesser Horseshoe Bat.